Despite challenges in accounting for returns and benchmarking performance, alternative asset classes offer defensive or yield-oriented core strategies associated with large institutions along with lower macroeconomic and real estate correlations.

Download the Article in .pdf

Introduction

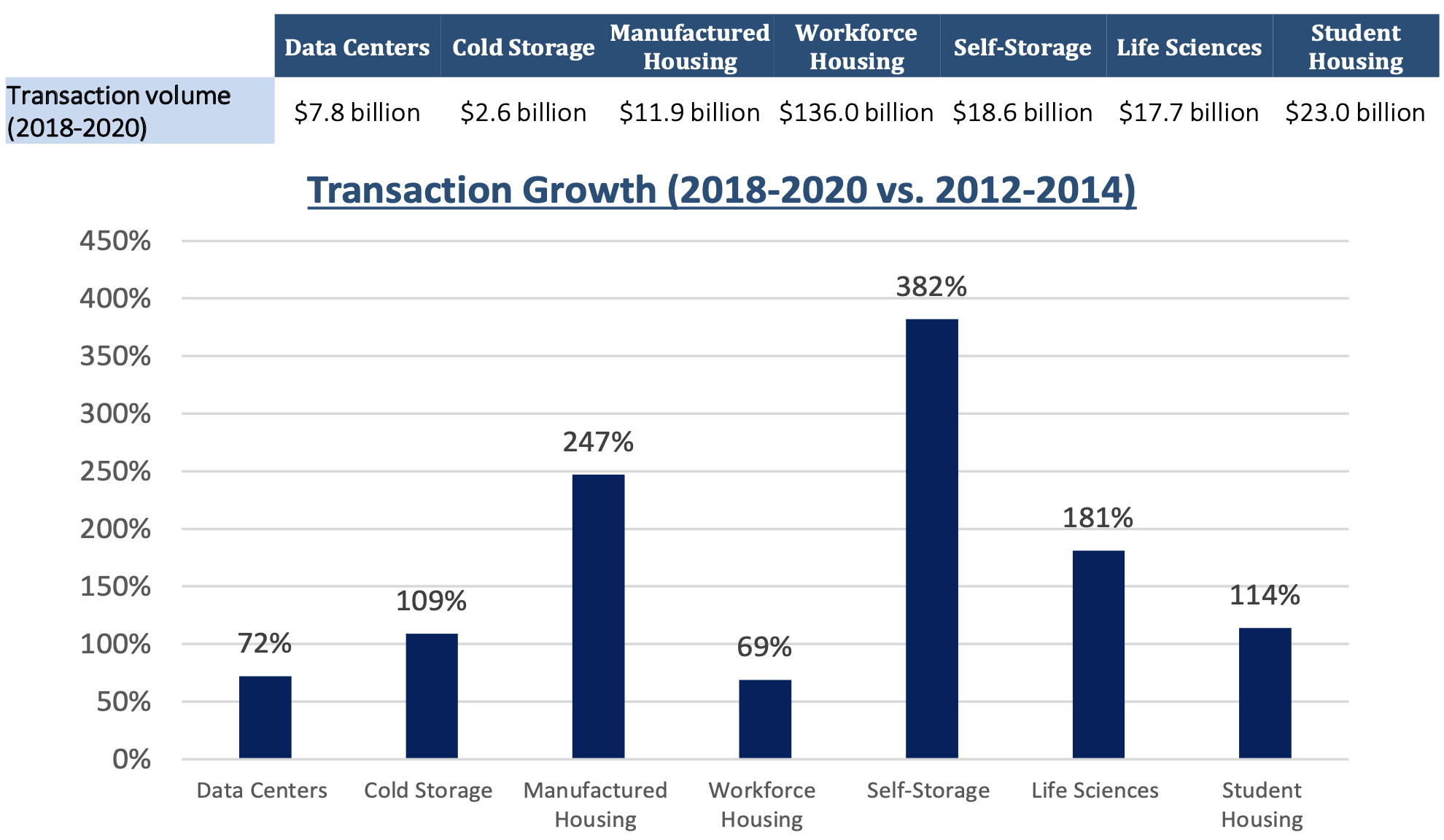

For longtime investors in alternative properties, the groundswell of institutional interest that started shortly after the Global Financial Crisis (“GFC”) has felt transformative—and the more recent COVID-19 environment has only accelerated this trend. In spring 2021, JLL reported that alternative assets (not counting workforce housing) collectively comprised nearly $48 B in volume—eclipsing the entire retail sector and amounting to 12% of transaction volume. The most widely followed alternative verticals like medical office, senior living, student housing, and self-storage have compelling historical outperformance in real estate fundamentals (ie, occupancy, rate growth, and NOI), and Virtus has published extensively (<a href="/2021-us-real-estate-outlook/"2021 U.S. Real Estate Outlook; Demographic Oriented Real Estate Investing and the Virtus Real Estate Capital Strategy 3.0) over the years explaining the Firm’s mandate to concentrate in these sectors. However, despite the rising allocations and increasing prevalence of major portfolio trades backed by major pension or sovereign wealth funds, the measurable performance advantage for alternative property types has been difficult to account for in the most central metrics: total returns. While much of this difficulty stems from the general lack of data transparency that characterizes commercial real estate, it also stems from a lack of obvious benchmarks suited to the needs of more core-oriented investors.

In this paper, we summarize the most applicable sources of data covering the historical returns of alternative sectors against the “basic food groups” within institutional portfolios. There is ample evidence of both higher returns and lower correlations within alternative

asset classes, but the entire industry still has progress to make before investors can better account for the impact of leverage or resilience of income returns in benchmarking alternative property sectors.

Figure 1: Alternative Property Investment Volume

Source: Real Capital Analytics

Historically, alternative property type (“alts”) have been mostly associated with either higher-octane or diversification strategies. Property types like self-storage and senior living have been justly valued for outsized returns, even in the historically strong market where

all sectors have been buoyed by the search for yield. Nonetheless, many alts are equally valued for their lower macroeconomic correlations, as well as their lower correlations to major real estate sectors. However, the relatively recent institutionalization of these sectors means historical performance benchmarks tend to be meager from both a timeline and thoroughness standard. NCREIF’s ODCE benchmark—the largest and longest running account of open-ended core funds—has fewer than fifty total assets classified as healthcare (including medical office and senior living) in it, representing less than half of one percent of the total index. In addition, property subsectors like medical office and workforce housing have only recently been recognized as distinct investment verticals, with most historical benchmarks considered generally unreliable in comparability past a few years of looking back. As such, the most frequent and available sources of data for performance benchmarks generally come from sources that are somewhat distanced from a typical open-ended core fund investment structure.

Many proponents of alts have pointed toward REIT portfolios as evidence from large, high- quality stabilized properties. However, there are very few pure-play REITs that focus on alternative properties, with most formed too recently for full cycle records. (ie, there is no true pure-play medical office REIT formed before the GFC). Moreover, public equities are inherently disconnected from private investments (in portfolio goals if not always correlations), so REIT evidence will always be an interesting, but not totally compelling, evidence source.

This was generally the problem that NCREIF’s NPI-Plus sub-benchmark was originally formed to solve. While NCREIF’s ODCE benchmark is generally too thin for statistically valid analysis, there is greater prevalence of such deals within the NPI dataset of funds, and NCREIF began tagging more of its dataset with subsector designations a few years back. While the NPI- Plus index itself is no longer published regularly, the practice of subsector designation has remained within NPI itself. As such, funds and assets from the NPI dataset form the most thorough evidence available for institutionally-held alternative assets, and most of the figures cited here and elsewhere derive from it. The obvious caveat is that the investment horizons, leverage amount, and income portion of returns do not perfectly match a typical open-ended core structure. Nonetheless, NCREIF NPI is currently the best overall evidence for the topline potential of alternative investments.

Full Cycle Evidence

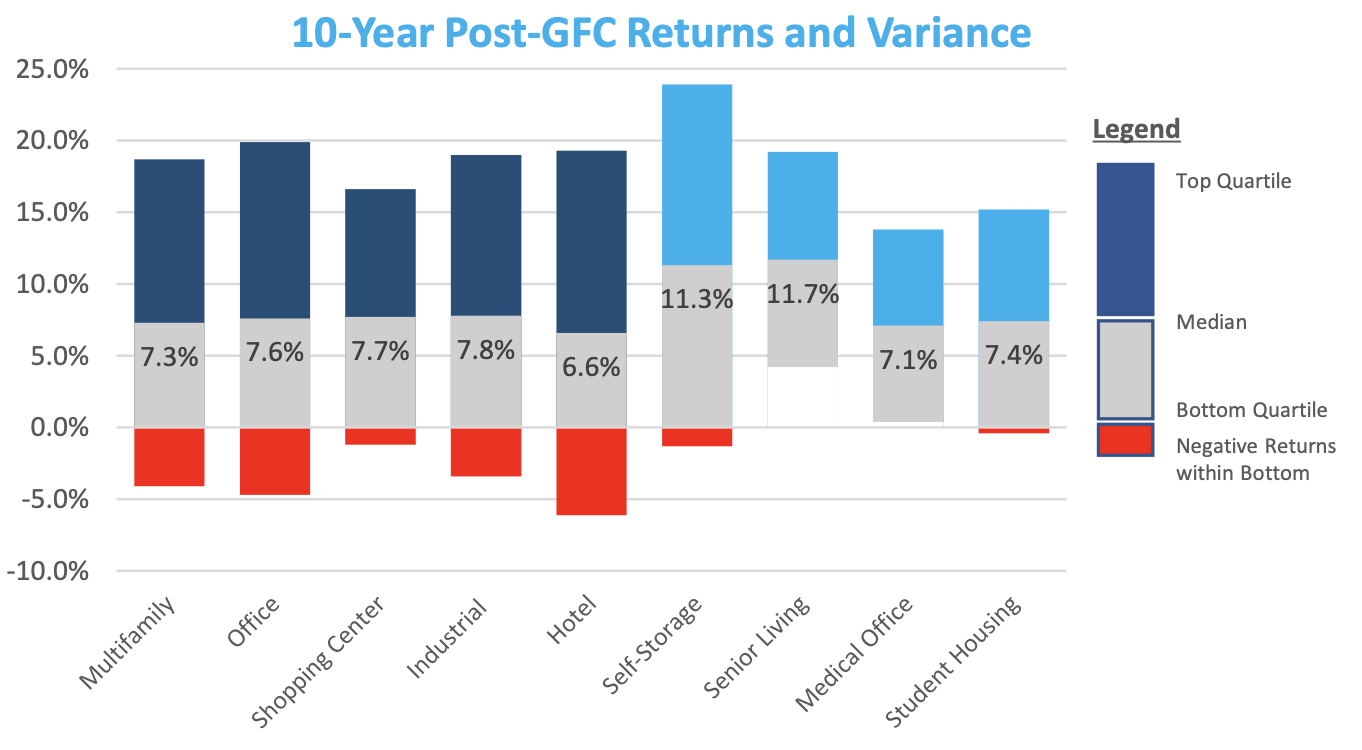

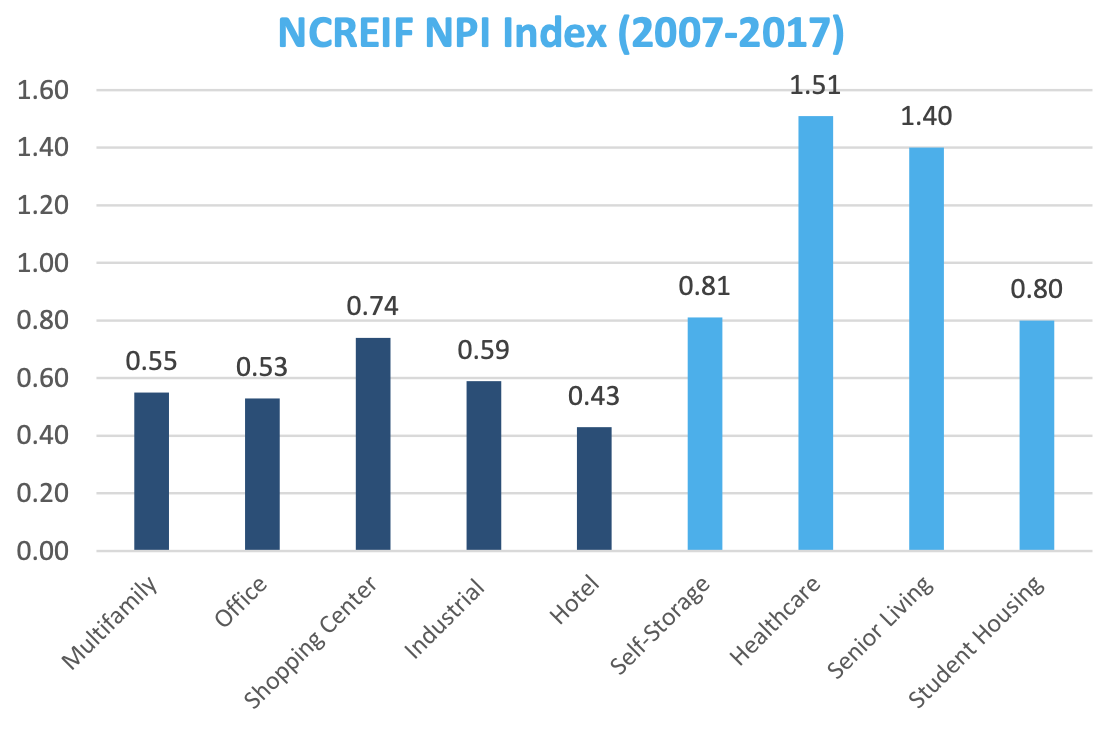

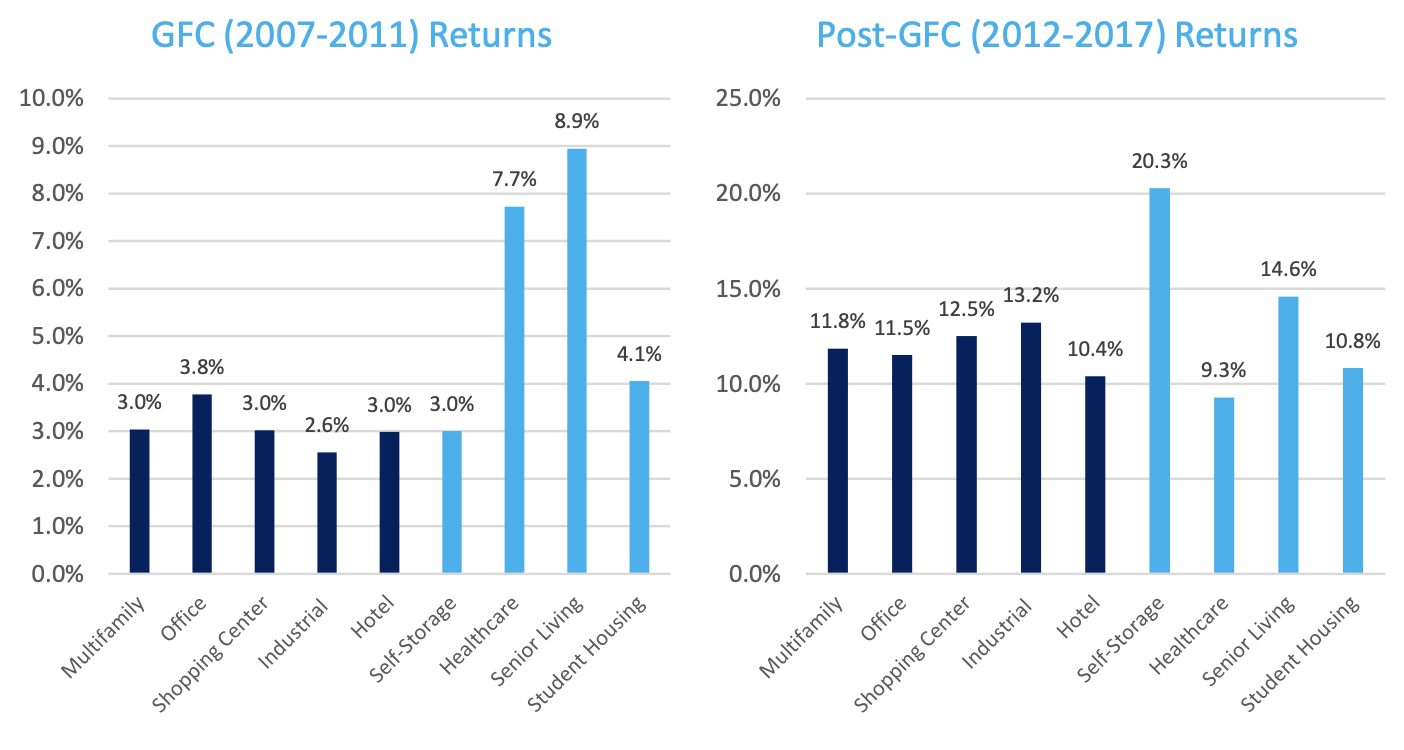

The most exhaustive benchmarking done on alternative asset classes within an institutional portfolio is likely still “Non-Traditional Property Types: Part of a Diversified Real Estate Portfolio?” by Will McIntosh, et al, published in 2017. This time frame made the 10-year total return lookbacks especially ideal for studying the full cycle of value erosion and subsequent recovery during the GFC. The authors were also able to access more granular property-level returns from the NCREIF NPI database than are typically reported, so their aggregation of sectors was both more statistically rich and detailed than previous efforts.

Their findings were extremely compelling: alternative asset classes were both higher returning than conventional sectors like office and were less correlated to both macroeconomic swings, as well as other classes of real estate (which largely correlate highly to each other). Figure 2 below shows the 10-year total return distributions (25th-75th quartiles) from the McIntosh study, with the alternative asset classes to the right having higher average returns, as well as much lower shares of negative returns. This dual outperformance is also visible in the authors’ calculations of Sharpe ratios for each class in Figure 3 on the next page.

Figure 2: NCREIF Returns by Property Type

Source: NCREIF NPI Index and NPI-Plus Index.

Figures cited from “Non-Traditional Property Types: Part of a Diversified Real Estate Portfolio?” by Will Mcintosh, Mark Fitzgerald, and John Kirk. The Journal of Portfolio Management

Figure 3: 10-Year Post-GFC Sharpe Ratio

Source: NCREIF NPI Index and NPI-Plus Index.

Figures cited from “Non-Traditional Property Types: Part of a Diversified Real Estate Portfolio?” by Will Mcintosh, Mark Fitzgerald, and John Kirk. The Journal of Portfolio Management

Figure 4: GFC vs. Recovery Returns

Source: NCREIF NPI Index and NPI-Plus Index.

Figures cited from “Non-Traditional Property Types: Part of a Diversified Real Estate Portfolio?” by Will Mcintosh, Mark Fitzgerald, and John Kirk. The Journal of Portfolio Management

Figure 4 shows that this pattern of outperformance held through both the immediate downturn environment of the GFC, as well as the subsequent recovery—showing that the alternative asset sectors were both more resilient to distress and did not perform solely

as a “defensive” strategy. Essentially, the authors confirmed that the largest alternative asset classes had returns that were both higher and less widely dispersed than institutional mainstays like office and retail.

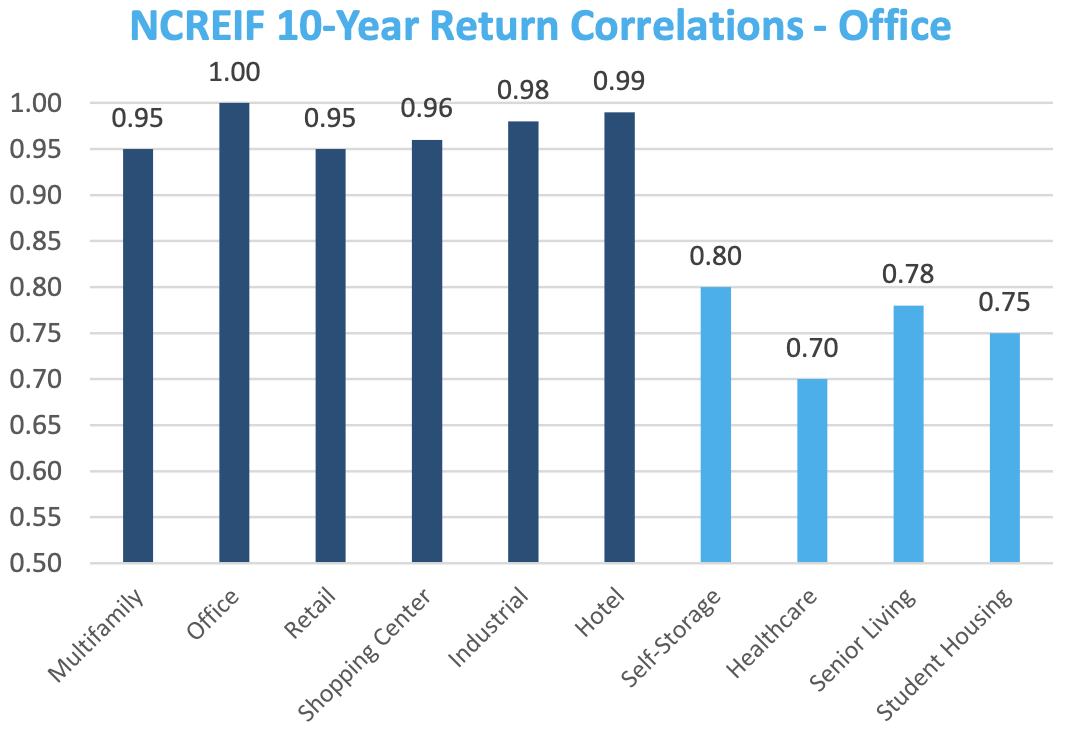

As mentioned, the authors also found that these higher returns were accompanied by lower correlations to conventional real estate sectors. Figure 5 below shows the above 0.95 correlations each major real estate sector has to office properties, compared to significantly lower correlations toward alts.

In short, the McIntosh research finds that alternative asset classes were an integral part of the efficient frontier for commercial real estate portfolios, at least through the lead up and aftermath of the GFC. But, what about more recent evidence?

Figure 5: Alternative Sector Correlations

Source: NCREIF NPI Index and NPI-Plus Index.

Figures cited from “Non-Traditional Property Types: Part of a Diversified Real Estate Portfolio?” by Will Mcintosh, Mark Fitzgerald, and John Kirk. The Journal of Portfolio Management

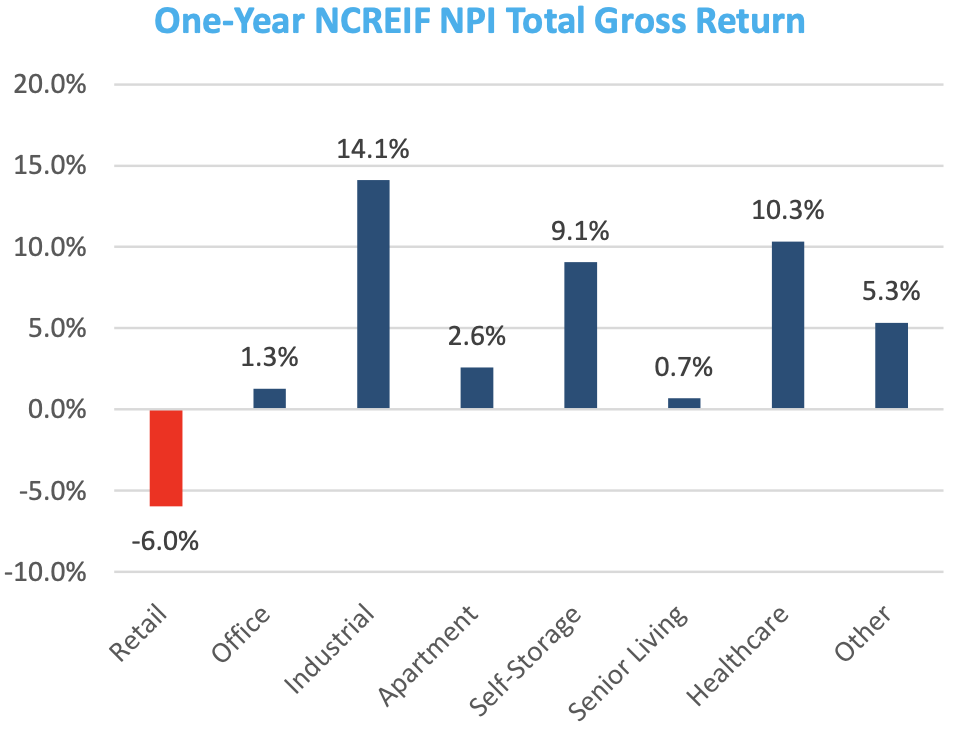

Updated Benchmarks and COVID-19 Era Returns

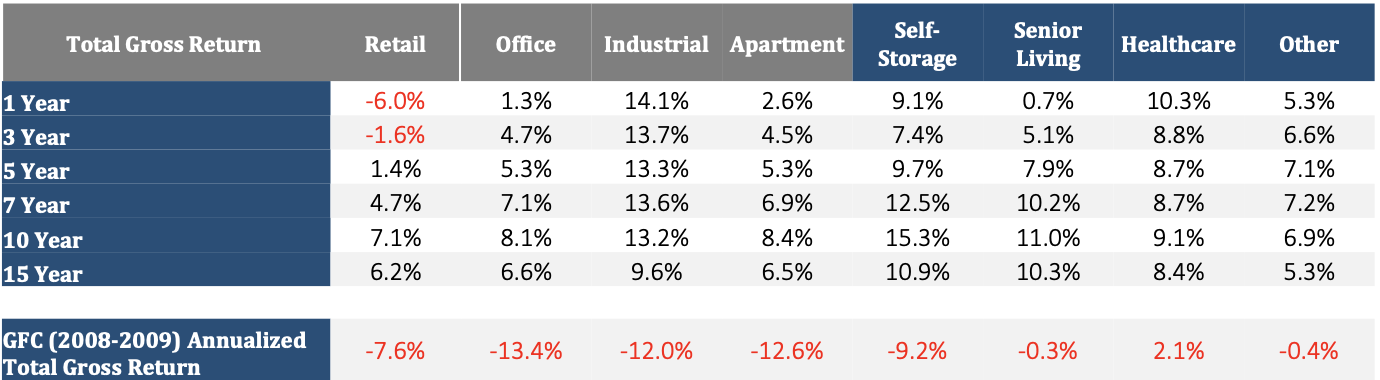

According to more recent figures from NCREIF, the relative advantage for alternative properties has held true through the COVID-19 pandemic, with only industrial assets outstripping alternatives. While only four years have passed since the publication of the McIntosh paper (rendering wholesale change in the results unlikely) there are still important developments to consider. For instance, during the immediate post-GFC period senior living assets had both the highest returns and lowest volatility among alternative properties. But, that time series fails to account for both the full crest of the sector’s record supply wave, as well as the outsized impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on the sector (especially in headline perception of risk). As such, it is not surprising that the one-year total returns as of 1Q 2021 show weaker performance for senior living assets compared to other alternatives.

Figure 6: Post-COVID Sector Returns

Source: NCREIF NPI Index and NPI-Plus Index. NCREIF NPI and NPI-plus quarterly updates

Nonetheless, the previous pattern has held through the current environment—a fact which is likely less surprising when considering how much the pandemic disrupted both office and retail properties. Since these two asset types comprise 46% of the ODCE index, it is not shocking that more and more institutions are seeking greater sector diversification or access to property types with fewer headwinds from macroeconomic forces or technologically disruptive trends like e-commerce and telecommuting, which have upended retail and office portfolios.

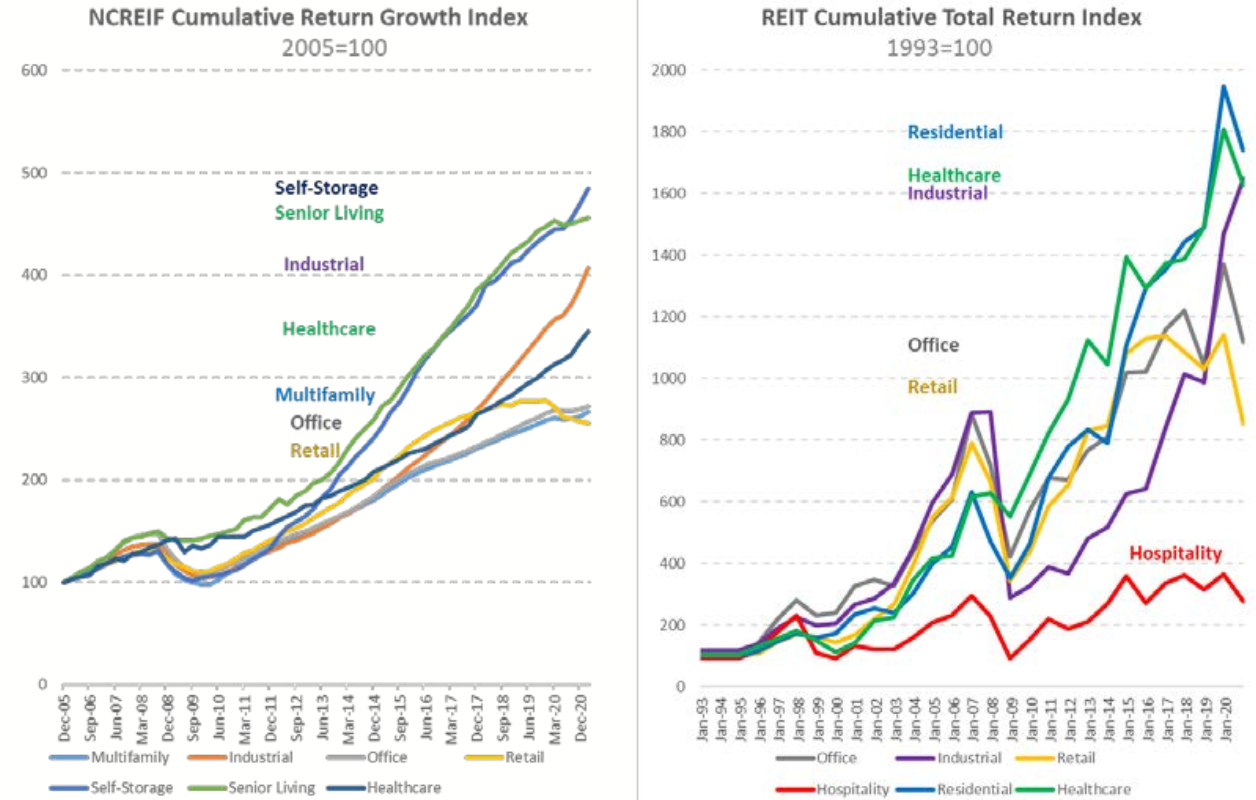

According to the best available evidence, alternative properties are well matched to these needs—with lower instances of value erosion during economic downturns, yet equally robust exposure to economic growth. This pattern extends as far back as NCREIF benchmarks are available for the largest alt sectors, as well as for public equities—again with the caveat that both datasets were not originally set up around these growing sectors, and as such their grouping of property types is suboptimal. For instance, the index aggregates both skilled nursing assets and outpatient medical office buildings into ‘Healthcare’ real estate, despite their very different operational realities and supply and demand dynamics. Moreover, the leverage ratios and income portion of returns from NPI portfolios are not perfect matches to the overall lower risk structures and longer time horizons that characterize core portfolios.

Figure 7: NCREIF Total Return by Sector

Source: NCREIF NPI Index, via NCREIF Quarterly Return Updates

Nonetheless, as total deployment continues to grow, it is likely the depth of evidence will become more detailed and complete—as well as boosting overall liquidity and adding even more momentum to the capital uplift portion of returns. Since the more direct fundamentals advantage of alternative property sectors is already better established, the emerging evidence suggests a holistic advantage for alternative sectors in direct performance, valuation resilience, and total returns.

Figure 8: Private and Public Index Returns

Source: NCREIF NPI Index and NPI-Plus Index. NCREIF NPI and NPI-plus quarterly updates. REIT returns via NAREIT.com

Contributors

-

Terrell Gates

Founder & CEO

-

Zach Mallow

Director of Research