Recent years have seen immense investment interest in rapidly growing markets outside the general Tier-I “Gateway” commercial real estate markets. However, with a climate of renewed uncertainty and risk-aversion, many investors are wondering whether this trend was specific to the post-COVID-19 environment, or whether it derives from factors with more persistent momentum.

In this whitepaper, Virtus explores the case for a new class of markets that have benefited from patterns in demographic growth, regulatory policy, and technological advancement over a much longer horizon than the recent past.

Download the Article in .pdf

Executive Summary

There has long been a question of whether the primacy of “Gateway” markets for commercial real estate investment is well-founded, or if it’s merely a self-fulfilling prophecy based more on capital market flows rather than true market fundamentals. Prior to the onset of COVID-19, there was certainly evidence supporting both sides of the argument. In the immediate aftermath of the upheavals that started in 2020, a curious pattern emerged: whereas prior downturns had seen a liquidity freeze with only slight warm spots in the most established markets, the pandemic period saw a clear preference for smaller, less dense, and faster growing markets. These types of areas also saw better performance in fundamentals— directly a result of COVID-19 lockdowns that made dense urban living more difficult and less appealing. As such, the aftermath of this aftermath poses a quandary: has the recent appetite for markets like Dallas or Nashville (versus New York or San Francisco) been a situational fad that will see a reversal? Or does it reflect a more fundamental shift in market primacy for commercial real estate?

The concept of Gateway markets originated during a time when the total growth of the American economy was at a much higher level, whether in more abstract indicators like GDP or more concrete ones like population or wage growth. As such, it has always been safe to assume there is more than enough of everything—capital, tenant demand, etc.—such that the highest profile markets will reach their capacity in any metric, and “spillover” will be collected by lower quality markets. For instance, a corporation will start its highest profile staffing in a Gateway market like New York City, and once its space demands exceed profitable tenanting there, it will begin leasing space in lower “quality” markets at lower cost of occupancy for lower compensation employees. Similarly, investment managers have historically looked

to deploy capital first into Gateways and then into less liquid, supposedly less “attractive” markets seeking lower valuations and higher yields. However, as the macroeconomic and demographic growth of the U.S. has settled, this spillover concept seems to have lost its momentum. First, lowered rates and changing patterns of population growth have dampened the topline growth potential of Gateway market fundamentals. Next, major corporations (especially key “future-building” ones) show an increasing preference for “growth” market locations for reasons beyond cost and low barriers—and increasingly for headquarters rather than just lower wage outposts. And finally, investment markets are reflecting this shifting primacy in both the total aggregate volume existing Gateways attract, plus the timing and pattern of appetite through cycles. All these trends suggest the lingering mental model of what Gateway markets are and are for is in danger of falling behind the rapidly changing times. We explore these ideas below while suggesting the emergence of a class of “New Gateway” markets that have practically taken the mantle of “highest priority investment locations” in recent years. In sum:

- The transaction patterns favoring smaller, Tier II “growth” markets were not solely a product of the COVID-19-period preference for less dense areas. Like many similar trends, this pre-existed the pandemic and was supercharged by it.

- The recent dominance of growth markets is not solely due to their top-line growth metrics but derives equally from their resilience of performance and investment liquidity.

- Changing patterns in employer location choice (including the increasing importance of employee preferences) is also driving this trend.

- The result is a new paradigm where traditional Gateway markets are no longer the clear “first stop” for generalist investors. The parallel conclusion is a new class of resilient growth markets that exhibit strong fundamentals and liquidity have emerged that appear to be at least on par with traditional Gateways.

Introduction

What is a Gateway?

Gateway markets are large, liquid, and supposedly the most natural places for institutional and international generalist investors to get exposure to U.S. Real Estate. Practically, this means major financial centers with long histories of investment interest; New York, Los Angeles,

and San Francisco are undoubtedly on the list. However, the standard quickly begins to fray when discussing other metros frequently included. Is Chicago still a Gateway market despite its economic and fiscal declines? Are Boston and Miami Gateway markets? If you’re heavily into education and biotech (or else “destination / lifestyle”) cities, you may be inclined to include either of these markets—both of which are smaller than many places considered too “Sunbelt” to be Gateway cities.

Indeed, the very concept of Gateway markets is contrasted less with “Anytown, USA” markets and more with Sunbelt growth markets—places like Atlanta, Dallas, Nashville, and Virtus’ hometown of Austin. Gateway markets solidified into a concept during a time these other metros were already acknowledged for their growth potential—but less so for their capital preservation or economic resilience. This existing narrative suggests Gateways are good places to park capital passively and over many years, whereas “growth” markets require more careful cycle timing and asset-level business plans, especially given heightened new supply risk presumably due to lower barriers to entry.

The emerging question is: does this pattern still hold? Are places like Chicago, Washington D.C., or Miami superior places for yield and capital preservation compared to places like Dallas or Atlanta? Even many institutional allocators would increasingly say “no” to this specific question. However, recent market trends are raising the same question about “true” Gateways like New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Headwind factors like corporate relocations

and anemic population growth have displaced many former selling points of Gateway markets into growth market alternatives. Nor are such markets still the undisputed financial centers for growth engines like technological innovation, supported by ensuing venture capital.

This process has been lengthy and persistent enough (and was supercharged by COVID-19) that places formerly seen as volatile boomtowns are currently behaving with greater resilience in fundamentals than their traditional Gateway counterparts. Moreover, Gateways suffer from their own success in attracting enough capital to increase cyclical behavior through valuations—meaning their increased appeal is more in catching the full amplitude of economic swings, assuming an investor can properly time them. All of this is very much opposite to what their fundamental appeal is supposed to be: as consistent places a non- expert can deploy large amounts of capital and still sleep well at night.

Skeptical readers may rejoin that any sector whose investment standard is “sleeping well”

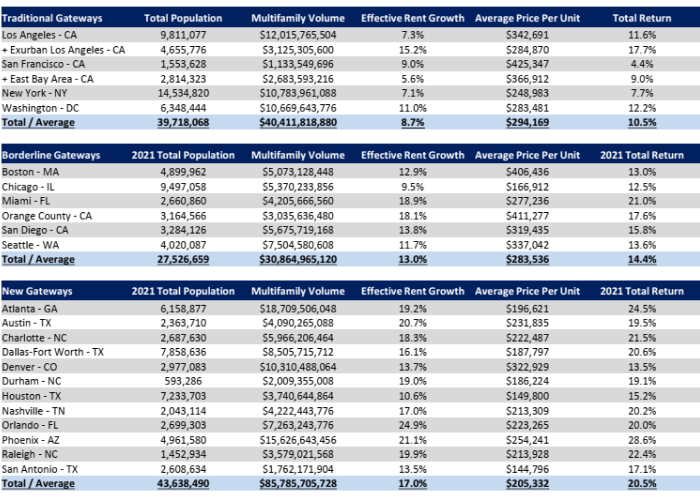

is going to run afoul of the current environment, but this is more reason to take a moment and consider whether past attitudes or standards still make sense today. Below is a table categorizing the nation’s foremost real estate investment markets by their “Gateway” status. While some disagreements on placement are inevitable, the calculations that follow derive from this grouping. We will show that “traditional” Gateways are in fact less robust in fundamentals performance, less liquid on a population-weighted basis, and less accretive in total return. Indeed, a deeper look shows how few of the traditional Gateway virtues “true” Gateway markets currently offer and how many challenges they pose:

FIGURE 1: 2021 PERFORMANCE BY MARKET TYPE(1)

FIGURE 2: 2021 MULTIFAMILY FUNDAMENTALS AND INVESTMENT PERFORMANCE(2)

The Volatility of their Performance

Perhaps the biggest paradox of this trend is that cities recognized as international capital havens will experience increasingly vast waves of capital against limited, high barrier stock, thus driving valuations to record highs in good times and seeing major capital pullbacks in bad ones. This may boost the cyclical behavior inherent to real estate, in that these markets are ironically more volatile and sensitive to macroeconomic conditions than the nation at large.

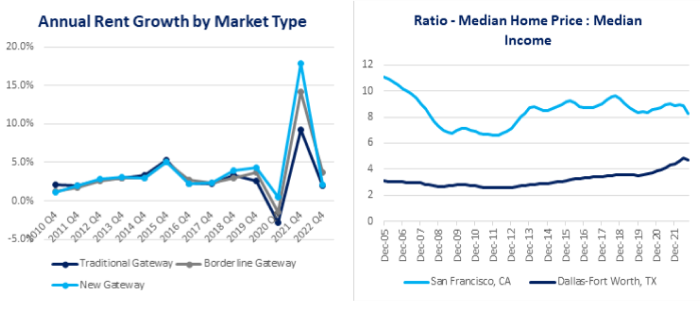

FIGURE 3: ANNUAL RENT GROWTH VS MEDIAN HOME PRICE(2)

Indeed, the valuation cycles Gateway markets currently experience prove this on multiple metrics. At the broadest level, home values in such markets are vastly more reactive to economic trends than the underlying incomes. The San Francisco Bay Area is the poster child for this trend; plotting typical home values against median incomes shows that San Francisco has historically been a great investment over the long term, but the ride is less “bumpy” and more of a rollercoaster.

Interestingly, this behavior was seen even during the Global Financial Crisis (“GFC”), but with the saving grace that liquidity returned to Gateway markets more rapidly than others.

The COVID-19 aftermath broke from this trend, in that Gateways suffered the same pullback, but the recovery was faster for more affordable and growth-friendly regions (which were associated with fewer difficulties during quarantine than high urban density areas). Growth markets have been cresting upward in total. This poses a problem: in recent years, Gateway markets have been attractive because of their volatility, rather than their stability. During COVID-19, rent growth was most downwardly volatile for true Gateways, yet their 2021 recoveries were far lower than that of other markets that had just been more resilient during the downturn. Volatility can be great when it comes with excess returns, but this is chiefly

a self-fulfilling prophecy: New York will always be a superior real estate market, not because

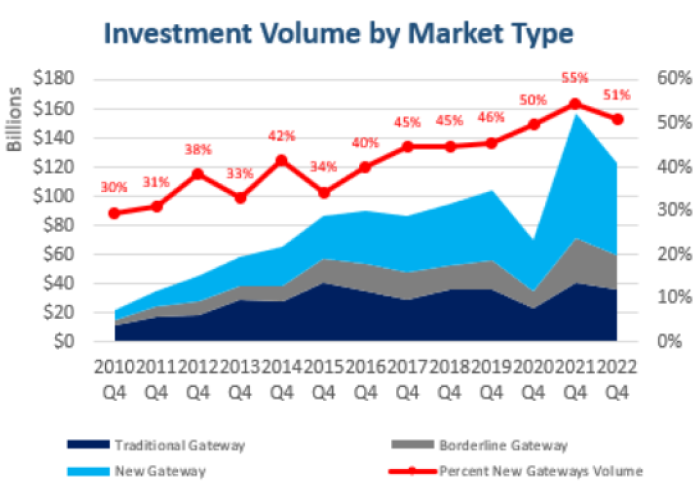

it behaves in a superior fashion, but because investors will always see it that way. However, both fundamentals and even investment appetite in recent years have shown this attitude to be changing. “New Gateways” have overtaken traditional ones since well before the pandemic—and interestingly they do so dramatically on a population-weighted basis. Traditional Gateways saw $40 billion in total multifamily volume during 2021 from a combined population of 39 million, whereas “New Gateways” saw $85 billion from a combined population of 43 million—a great advantage in liquidity and arguably market diversity.

There are several overarching factors driving tenancy demand (and capital with it) away from Gateways on a relative basis to new Gateway markets among others. They can be summarized as quality of life, cost of living for employers and other stakeholders, more friendly regulations, cost of occupancy for commercial tenants, and stronger property rights protections. COVID-19 accelerated a trend already in place for people departing the Sunshine state and heading to greener pastures in places like Texas and Nevada. The only way California has maintained its population is from offshore in-migration. What’s particularly concerning is the population loss has been highly-concentrated with high skilled jobs and especially entrepreneurs and owners of established companies relocating for lower taxes and better quality of life. Even the natural beauty of California and the near perfect year- round weather hasn’t been enough to keep major private equity, venture capital, and other investment managers to not only relocate ownership, but in many cases to bring their teams as well as many of their portfolio companies. When you compare a 13.3% state income tax and state cap gains tax for the top “one-percenters” to zero in a place like Texas (despite the higher property taxes), and overlay with a far more business-friendly regulatory framework, for many business owners, large and small, the decision eventually becomes a “no-brainer” in some cases. For reasons below, many commercial real estate purchasers seem to be following suit.

The Growth Prospects

In the past, growth markets producing higher percentage gains on any metric (rent, population, valuations) could be explained simply as the advantage of small numbers, which are easier to lift in relative terms.

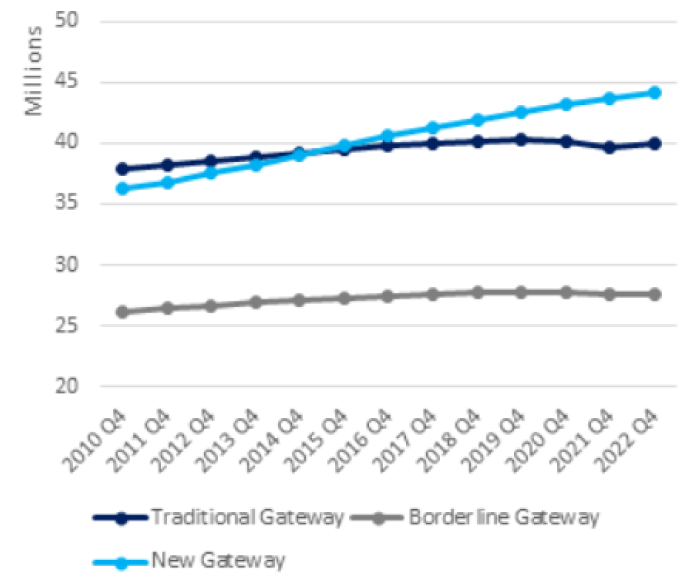

FIGURE 4: TOTAL POPULATION BY MARKET TYPE(3)

Decades later, places like Dallas and Atlanta are Top-10 metros by population, yet they continue to draw more numbers on both nominal and percent terms. Indeed, whereas

these markets were formerly seen as natural growth centers merely for being cheaper, less regulatory, and more land-rich, there are increasingly structural reasons they benefit. A place like Raleigh has an ecosystem for biotech R&D unrivaled anywhere besides Boston and the San Francisco Bay Area, yet its population growth prospects dwarf both more established places. Austin has grown an increasingly diverse tech ecosystem, now seen as a top talent hub for established companies, along with a vibrant venture capital ecosystem to support smaller startups. In short, the growth market “advantage” may have begun solely from cost advantages, but there are now compelling positive reasons for growth—even while such areas skyrocket in costs and raise development barriers. The result is an entirely different growth trajectory for traditional Gateways (which are shrinking in population) versus new Gateways, which have taken the lion’s share of population growth in a climate of anemic birthrates and declining immigration(4).

Changing Patterns in Work and Demand

The factors above derive from broader, less local trends that also favor “New Gateway” markets. First, market location is a more holistic process. In the past, employers drove

location choice in a top-down fashion: logistics, infrastructure, and tax/regulatory scheme are balanced against the economic “gravity” of more established locations, and a location decision is made for its real estate. In recent years, it is increasingly being driven by employees making lifestyle and cost-of-living decisions, and hence the employers must respond to such and locate in those markets to have a better shot of recruiting and retention.

It is also worth mentioning that while traditional Gateway markets have always been associated with higher barriers, the extent and type of those barriers have also increased in recent years.

Places like New York will always have higher taxes, but recent years have also revived concepts like rent control, more stringent anti-eviction policies, and various development limits that all effectively make commercial real estate ownership riskier, and with more exogenous risks outside operational control. Further, these same markets are also increasingly regulatory in their involvement with tenants, especially those in complex or future-building sectors. While the near-wholesale move of the various firms owned by Elon Musk to less regulatory states has had an undeniable element of corporate theater, the underlying reasons are still very clear: it is much easier to operate such complex firms in a less regulated environment. Finally, these trends are self-reinforcing, in that they create a more diffuse workforce that is less dependent on physical “hubs” of major office markets, such as New York or San Francisco. Technology builds the momentum of this trend as well.

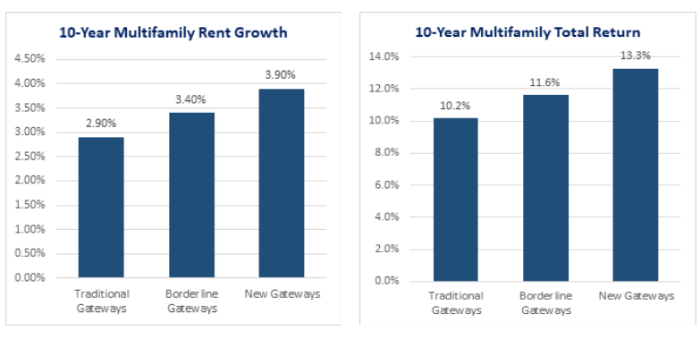

FIGURE 5: 10-YEAR MULTIFAMILY RENT GROWTH VS MULTIFAMILY TOTAL RETURN(5)

While many employers may bemoan the increasing use of video teleconferencing over physical meetings, these technologies nonetheless make it much easier to coordinate efforts between cities, or continents for that matter. Whereas the productivity difference of Zoom or Teams versus in-office presence is somewhat murky and sector-dependent, it is a clearer value proposition between locating an office in Manhattan or Dallas. In short, the paradigm that drove Gateway markets was that of a less connected world where there was more obvious value in office hubs.

Aside from their supposed risk-minimization, traditional Gateway markets should also offer a comprehensive breadth of strategies for investors with different needs in terms of yield, risk, and overall return. However, the range of strategies they pose is practically limited by their low rates of growth.

The tables on the previous page suggest that anemic growth is being reflected in both total rent growth and total return as measured by CoStar. Gateway markets have seen declining populations, and while they may post dramatic recoveries after pullbacks, their long-

term total returns are hampered by their dramatic downward cycles. Historically, capital appreciation (primarily from compressing yields) has made up for this anemic top-line growth, and perhaps it will continue to do so in strategies most germane to institutional investors. However, those same institutions will still need to find other avenues of deployment to meet their full needs in total return, meaning they will be unable to avoid the extra “headache” of studying emerging metros.

In short, Gateway markets are increasingly limited in their abilities to provide large investors with a total real estate solution, and they increasingly display behavior that is antithetical to the “deploy and sleep well” strategy they are associated with. Without the growth potential, capital value resilience, or robust yield Gateway investments are supposed to offer, what remains of their appeal compared to other markets, aside from high nominal valuations that allow the largest investors to deploy more rapidly?

What are the New Gateways?

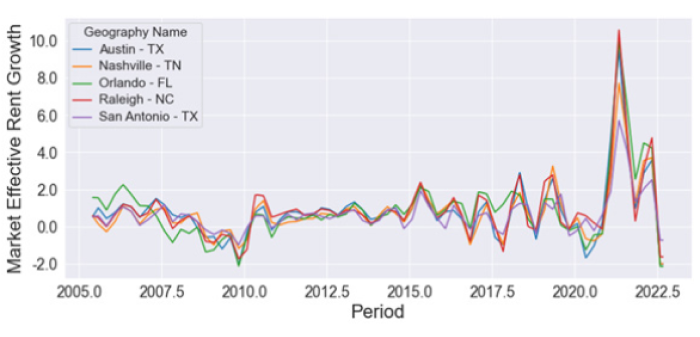

It would be reductive to claim the central thesis of this paper is that “growth markets are the new Gateways.” Then again, investment appetite in the pandemic’s wake (and the wake of the subsequent “recovery”) suggests that such markets are already behaving as such. In the immediate post-COVID-19 period, the nation saw an immense population migration away from higher density areas into lower barrier, lower cost markets. Many of these areas were genuinely outlying, but there was a “sweet spot” in the overlap of metros that were thriving and still had institutional liquidity. Many of these markets already had a significant footprint in sectors positioned to grow through the times—chiefly technology and healthcare, with biotech as the ideal confluence of these tailwinds. As quarantine subsided and the recovery progressed, these markets then partook in the same “catchup” all other markets did—with the result that their cumulative outperformance makes them obvious winners of this unprecedented period—and moreover, this period was simply the capstone to several decades of offering similar outsized returns. Markets like Austin and Raleigh have consistently been “the next big thing” in real estate for several cycles, and with each cycle, they get closer to being the big thing itself. If there is any doubt that such markets are a class unto themselves, see the figure below tracking historical rent growth across them(6).

FIGURE 6: NEW GATEWAYS RENT GROWTH(6)

The remaining question is more “why would an investor place capital anywhere else?” And frankly, the answer is simply that there are only so many opportunities in the Austins and Raleighs of the world. One could also reference the historic volatility these markets experienced prior to the GFC, but that was during a period where their infrastructure, diversification, and overall gravity were far less developed than they are now. The “top priority” for capital in recent years has been less for Manhattan than supposedly “second tier” markets that nonetheless offer the highest in both cycle resilience and total growth potential. In some cases, only after these highest potential efforts are exhausted do managers seeking top quartile performance turn their attention to traditional Gateways.

Even here, though, there are non-Gateway alternatives to the goal of a resilient portfolio at the investor’s ideal place long the risk-return horizon. While cities like Austin, Nashville, and Raleigh offer unparalleled relative growth figures, other markets like Dallas, Atlanta, and Denver offer similar opportunities that formerly came chiefly from Gateway locations. While these cities also post extremely robust population gains, they differ from the above cities in that their economic gravity is less defined by future-building growth sectors and more by a resilient base of existing large corporations. Often, this presence started as an overflow location for “cheaper” personnel years ago, but lately these locations are becoming true corporate headquarters—as evidenced by even CBRE moving its headquarters to Dallas. To be fair, some of these cities are not as diversified as others; for instance, Houston is highly dependent on both the energy sector and international trade (both of which have high macroeconomic beta). However, even “true” Gateways have these risks: San Francisco is now indelibly bound with the tech industry, and New York is still highly tied to international finance. And both tech and international finance have become more diffuse over the years, and this trend was only catalyzed by COVID-19.

To be clear, nobody is arguing that an Austin ever replaces New York as the obvious first stop for an overseas investor looking to deploy capital in the U.S. New York has a far deeper property set, with greater density, greater demand of existing tenants and capital, and it would be a fool’s errand to ever state that New York can be replaced by any one of these new Gateway markets in the foreseeable future. But the vector of this evolution to new Gateway markets is palpable and should be considered for long-term demand by tenants, and the capital that chases built space.

Conclusion

The emerging picture is one where no single city or small city group covers a landscape of total resilience, and investors should deploy across a range of geographies. And once this music is faced, the primacy of traditional Gateways as a one-stop solution to U.S. real estate diminishes. In the current environment, the entire concept of passive investment is increasingly fraught with challenges and uncertainties that demand patience from a responsible portfolio manager.

While Gateway markets may have offered a less headache-prone investment strategy in the distant past, they currently pose different challenges than other markets, many of which are unique and demand close diligence—whether it be a dive into the fiscal and demographic challenges facing a market like Chicago, or else determining just how much a possible tech pullback would dampen the Bay Area as a whole. Again, this does not mean they are irrelevant or poor locations for capital deployment; rather, traditional Gateways are simply local markets like any other, with both problems and opportunities unique to them. And when viewed this way, they should be considered for their forward-looking fundamentals (rather than their reputation for safety), just like any other market should be.

Contributors

-

Terrell Gates

Founder & CEO

-

Zach Mallow

Director of Research